Hittites, Illyrians had common cults

filed under illyrians, hittites, ancient cults

Traces of Illyrians went beyond their historical homeland, in Greece, Asia minor, and Italy. Theories about this connection as well as their origin and formation have been divers. Some have seen them as part of the original Mediterranean population while others have held the view that they were part of a second wave of IE settlements...

The latter argument is more convincing because there are some signs which imply the presence of proto-Illyrians in and around Mycenae. The studies conducted by Milan Budimir, V. Georgiev, P. Kretchmer, P. Ilievski makes it known that certain Illyrians were to be found there as well. In a careful research, Petar Hr.Ilievski argued over the existence of certain Illyrian and Thracian names found on the Mycenean onomastics. The references of presence of Illyrian peoples in parts of Europe beyond the limits of their historical homeland have not received adequate research. sremains a challenge? John Wilkes would indicate, “the presence of Illyrian peoples in parts of Europe beyond the limits of their historical homelands, and also in Asia Minor...is yet to be interpreted…” (John Wilkes, The Illyrians, p.39) Even more challenging is the question of how Illyrians might relate to the Hittites. Were the two part of the same pre-historic population, or were the two neighbors with a similar culture? Below I will point out two cults the two peoples shared.

+ Continue reading

The Illyrians had two major cults, the "cult of the sun" in the north and the "cult of the serpent" in the south. Alexander Stipceviq, in his book, the "Illyrians", indicated that the Illyrians shared the latter cult with the Hittites. He referred to a neolithic figure discovered in the packed clay layer of a house in the Neolithic settlement, 'Tjerrtorja' on the outskirts of Prishtina. The fragmented body of the snake, which is missing its head, is decorated with zigzag incisions accompanied on both sides with vertical incisions. This snake doubtless served a cult purpose. (F. Doll, Decorations from snake house cult…, Prishtine, Thesis Kosova, no. 1, 2009, p. 129) Later, with the formation of the Illyrian etnikum, we also find the snake in figurative realistic representations in the silver bracelets found in the 6th-5th century BCE grave of a royal Illyrian couple in Banjë e Pejës. ( Doli, 129) Such figures, Stipcevic indicates have also been found in Mycenae. History does provide references of connections between the two peoples. Egyptian hieroglyphs shed some light about the Illyrian presence in Asia minor. In the thirteenth century BC, Ramesses, the Great of Egypt, fought a battle with the Hittites. It is pointed that Hittites had allies which the Egyptians recorded them as the "Drdny" (see Gurney, The Hittites). No other peoples resemble this name except for the Dardanians of Illyria. Based on what Stipceviq indicates even the Illyrian name has Hittite origin. He refers to K. Oshtir who indicated a connection between the Illyrian name and the ancient name of a Hittite mythical serpent "Illujankash". Supposedly this name took hold with the coming of Cadmus. The ancient writer, Apollodorus, recorded Cadmus (Illyrian?), coming to the aid of the Encheleae who were at war with the tribes from the north. Cadmus conquered these tribes and in his victory was named king of the Encheleae=eel men.

His wife, Harmonia, bore him a son, Illyrius. At birth, Illyrius was supposedly empowered by a serpent (Illujankash=Ilurjan?). The theme of the serpent does not end here. When Cadmus and Harmonia were punished by Zeus for past grievances, they were condemned to live out the rest of their days as serpents.

Some indicate that Illyrian Hittite connection is supported also by archeological finds. Some artifacts found within the vicinity of ancient Troy have been acknowledged as Illyrian proto-type. This association could be explained either through a shared kinship or an inhabitation close to each other.

Giuseppe Catapano, an italian phylologist, revealed some Hittite words found also in Albanian language. To indicate the present, the Hittites used the single sylable word "ni", which is present in as 'nitash' (north Alb.), 'tani' (south), nani (arvanite), 'nime' (centeral Alb.)... It is also pointed that Albanian language shares words 'urim=greeting' 'anie=boat'..., with the Hittite area.

It is interesting to note that the snake cult still appears as a special phenomenon in Albanian popular belief. Among the Albanians, the snake is closely connected with the home and the family. Thus, in popular Albanian rites and beliefs, the snake appears as a god protecting life, well-being and the good fortune of the family.(Mark Tirta, Mitologjia ndër shqiptarët, Tirana 2004, p.145.) Stipceviq indicated, that the serpent is presented as protector of the home, and personification of the deceased head of the clan. (Iliret, p. 319).

Another Illyrian cult that apparently is shared with the Hittites is the double-headed eagle myth.

The earliest depiction of the double-headed eagle has been traced on ancient Hittite monuments in central Anatolia. In the early 19th century, in Boğazkale, Charles Texier discovered cylindric seals with clearly visible two-headed eagle with spread wings. The double-headed eagle motif originally dates from c. 3800 BC. The Hittites are believed to have worshiped the double headed eagle as the King of Heaven, who was also called the Hittite Bird of the Sun. As Hittite Empire weakened (from the 9th century BC to the 7th century BC), use of double-headed motif starts to disappear, and by the time of end of the empire, its use disappeared totally.

Double-headed eagle motives from Illyrian inhabited territories:

1. VI c. BC -Croatia, 2. VI c. BC -Montenegro, 3. VI-V c. BC -Mat tumulus (Albania), 4. VI c. -Korce (Albania)

1. VI c. BC -Croatia, 2. VI c. BC -Montenegro, 3. VI-V c. BC -Mat tumulus (Albania), 4. VI c. -Korce (Albania)

By the 2nd century BC, the Romans took the name of Zeus under the name of Jupiter, and single-headed eagle became a symbol of the Roman state and the military legions. It was used throughout the Empire, including what came to be known as Byzantium. There is evidence that other entities in the Balkans took-up using it: 1. Bulgaria (Stara Zagora), 10th-11th century (Stone slab with Double-Headed Eagle). 2. Macedonian Empire in Bulgaria (976-1018) or from the time of Byzantine occupation (971-976 & 1018-1185) and may be the emblem of rank of the Bulgarian tsar/basileus in (the former prefecture) Illyricum (as described in: http://www.hubert-herald.nl/TwoHeadedEagle.htm). 3. The oldest preserved Nemanjic dynasty (wb-a a dynasty bearing an unslavic name) double-headed eagle in historical sources is depicted on the ktetor portrait of Miroslav of Hum in the Church of St. Peter and Paul in Bijelo Polje, dating to 1190. 4. Epirus, French, end of 13th century. Teca Aurea of Thamar Angelos Komnenos 5. The eagle (gold on a red background) was also used by the semi-autonomous Despots of the Morea and by the Gattilusi of Lesbos. (Mid-fifteenth century; by this time Morea was predominantly Albanian).

One can not escape concluding that the inspiration for the above double-eagle motives was the old local traditions. Apparently the new Slav settlers adapted the double-headed eagle from the indigenous population that they in time assimilated most of it. As for the source of the so-called "Byzantine" emblem some have gone outside of the Balkans. A decorative piece of art (made of gold-woven Byzantine Silk)), associated with the Paphlagonian city of Gangra (where it was known as Haga, Χάγκα) and thought to have been done during Emperor Isaac I Komnenos (1057–1059) is seen as the reemergence of the Hittite motif. Zapheiriou (1947) supposed that the Komnenoi (originally from Thrace but had aquired estates and settled in Paphlagonia, see Double-headed eagle, Wikipedia) brought the double-headed eagle motif to Byzantium. Thus according to this assumption it took almost 400 years for the Byzantines to adapt the emblem during thas century of the Palaiologos dynasty (1259-1453). At the same time, it is important to point out, that the only occasion the double-headed eagle appears on a flag is on the ship that bore Emperor John VIII Palaiologos to the Council of Florence in 1439. Zapheiriou's assumption is far fetched. As we have seen, the double-headed eagle cult had a presence in the Balkans from the earliest times, and the motive continued to inspire various entities in the area where the cult was originally practiced. Byzantines did not have to wait for the reemergence of the motive in Anatolia, it was among them all the time. As is known Gjergj Kastrioti-Skenderbeu adapted the double-headed eagle as his emblem; but the reason for this selection remains a mystery. Many have assumed that the Kastriots just copied the Byzantine emblem, for which there is no documented support whatsoever. Another view contradicts the latter assumption and states that the bases of the double-headed eagle selection goes into mythological "pelasgic" past. The following is a summary of an article that appeared in Studime Historike» 3, 1987, Tiranë, by Luan Malltezi The emblems of Medieval Albanian noble families indicate various themes and indicate no inspirational connection with Byzantine emblems: The first Albanian state that emerged during Byzantine reign, that of Arber, had a different emblem. Muzakajt ended up using the Byzantine emblem, after being rewarded this right, as recognition of their authority, for the help Andrea II Muzaka had given the Byzantines in their fight against Vukashin. The Chronicle of Muzaka also made clear that this choice replaced their original preference "the renown Epirioten spring that turns on and off that many ancient authors had referred to". While Topias ended up adding to their emblem also the House of Anjou flag. Thus, these emblems basically reflected ruling families' history and political interests.

The case of Kastriots is seen as somewhat differently; they were new in the scene, entering the political history with Gjon (Gjergj's father). Kastriots had not served the Byzantines to aspire the use of their emblem; and what's more important at their time, Byzantine authority was in decline, at least in Albania. What value would the Byzantine emblem have in their dealings with other Albanian fuedal chiefs? How would the Kastriots justify this emblem with Dukagjins, Muzakajt, Arianits, Balshas, etc...when the latter new that their family (Kastriot’s) had no connection at all with the Byzantines... If the emblem of Kastriots was not borrowed, what was it then?

It could be an emblem inherited from the feudal chiefs on whose domain the Kastriots extended their authority, but the meaning of their emblem could go deeper in time. A series of indirect pieces of information that point to a process similar to the creation of Muzaka's original emblem (the spring with two torch-bearers)...thus, reflecting a historical connection in their emblem.

First, the fact that Barleti gives: the name Skenderbe...was given to him... and with this name they had in mind Alexander the Great of Macedonia. (Iskender corresponds in Turkish to Alexander; for the loss of “I” see Sh. Pllana. Skënderbeu në krijimtarinë gojore të Kosovës dhe të Maqedonisë, në Simpoziumi për Skënderbeun. (9-12 maj 1968), Prishtinë, 1969, f. 298.)

Apparently, the Turks related Skanderbe to Alexander the Great. Was this fortuitous? What bravery would a 9-year old boy, the young Gjergj, have to deserve such an enormous name as that of Alexander? In Barleti's book it is clearly indicated that Albanians considered Alexander the Great as their own...and this is referenced on a few occasions. (During the encirclement of Sfetigrad, the Albanian commander indicated to his soldiers the “the Persian King Dari also fled after being defeated by our Alexander… (M. Barletius. Historia de vita et gestis Scandergegi Epirotarum principis…, Tiranë, 1967, f. 224.) By his time chronicles and ancient greco-roman authors, their great historians and philosophers, together with their heroes and artists, and together with them ancient names of peoples and places, that time had left them in the distant past, were redescoverd... In this opening to the past, Albanian humanists took the job of finding the historical roots of Albanian people; (E. Dule. Koncepti Epir dhe epirët në shek. XIII-XVI 1982) ...they concluded that the Albanians were direct descendents of the ancient Epiriots and Macedonians, of Pyrrhus and Alexander the Great. The latter, the chronicles and ancient historians indicated was a pure Epiriotan through his mother. (Thus Alexander the Great was also Epirotan by his Aeavidean mother. (Pausania Deseriptio Graeciae..., Ilirët dhe Iliria te autorët antikë. Tiranë, 1965, f. 241) For the Albanians of the XV, who identified themselves as Epiriotans, this relationship was sufficient reason to consider, Alexander the Great, like Pyrrhus, a glorious Epiriotan descendent...Thus there was a reason why Ottomans named Gjergj Kastrioti, Skenderbe (=Alexander).

An important question would be, that is if the name was given because the Albanians considered themselves his descendents (Alexander's), or that Kastriots themselvs pretended to be... that they were his descendents? Both options could have pertained. The fact that he kept the name Skenderbe all his life (He used this name in his correspondences, and others addressed him with the same name, J. Radonic. Gjuragj Kastriot Skendërbeg i Arbanija u XV veku. Beograd, 1942), leaves us to conclude that he considered himself to be a descendent of Alexander. It would appear that the well known symbolism of a goat with two horns in his sallet was adapted for the same reason. The Kosovar researcher, Sh.Pllana has given interesting as well as adequate reason to maintain that his sallet was in essence Skenderbeu's recreation of Alexander the Great's sallet, whose name he bore. (For more on Albanian traditions on Skanderbeou’s sallet see Sh. Pllana. Skënderbeu në krijimtarinë gojore të Kosovës dhe të Maqedonisë, Simpozijum o Skederbegu (9-12 maj 1968), Prishtinë, 1969, f. 287-301, see Plutarch’s reference to Pyrrhus sallet Ilirët dhe Iliria te autorët antikë, Tiranë, 1965, f. 223)

If Skenderbeu considered himself a descedent of Alexander the Great..., why it wouldn't follow that he would create an emblem or a flag in accordance to military symbols of Alexander and Pyrrhus at a time when they had wide acclaim with XV century Albanians... ...There was a model for Kastriots to imitate or copy. The model was offered by Pyrrhus, an Epirioten (Molossian), head and feet related to Alexander, whom, as we mentioned above, the Albanians of XV century, as Barleti indicates, considered their direct predecessor. Gjergj Kastrioti would write to the Terentian Prince in 1460 in response to prince's letter..., "if our chronicles are to be believed, we are called Epiriotens, and you should know that in the past our forefathers have crossed over to the land which you hold today and have fought big battles with the Romans, and it is well known that most of them we ended honorably for them.” (Historia e Shqipërisë,Tiranë, 1967, f. 300) The fragment is a clear allusion to Pyrrhus. Thus, it is not only Barleti, as man of letters and classical culture, that was attracted to Pyrrhus and Alexander... but it is also Skenderbeu himself, first as a statesman, and with him the conscientiousness of the society of the time, which emanated the same thoughts...

Plutarch, writing about Pyrrus, indicated that when Pyrrus retured back home gloriously "the Epiriotans greeted him with the name eagle, he responed that it was their merit that he was an eagle, and how could't I be when you and your arms have risen me high as with fast wings.” (Historia e Shqipërisë,Tiranë, 1967, f. 300) This attribution would be an adequate inspiration to create an emblem focusing on an eagle... There is an additional indirect detail in support of such a possibility: Skenderbeu's stamp, known as his "secret stamp". Similar to the his big official stamp, it has been extracted from the wax on a letter Skenderbeu had sent to Ragusa around 1459. It is thought that the stamp had also served his father, Gjon... According to scholars the stamp borrows a mythological theme, it shows Leda (Anatolian princess) and Zeus standing-by (transformed into a swan). This is definetly a theme from antiquity, more specifically "pelasgic", and indicative that the Kastriots went deeper in history in search of their ethnic links. It is most probable that they followed the same process in selecting the double-headed eagle motif for their emblem and flag. And for this they did not have to go far back in history. As we indicated above, the double-headed eagle was a major cult with the Illyrians.

Medieval Kosovo

filed under Kosovo, Medieval Kosovo

+ Continue reading

There is no basis to assume that the area was unpopulated or that the original inhabitants had left the area after the Slavs came. At least for the case of Kosovo, knowledge that has come to light after WWII has tended to support the view that the original population had survived the Slavic onslaught and had continued to inhabit the area throughout the middle ages. Here is what well known Yugoslav historians have noted about the survival of the pre-Slavic population of the area. Fannula Papazoglu has indicated that Dardania was one of the Balkan regions less Romanized and that its population seems to have preserved better its individuality and its consciousness from antiquity, and the possibilty that the Dardanians were able to escape Romanization and to have preserved its individuality, cannot be excluded.(Iliri I Albanci, Belgrade, 1988, p. 19) Henrik Baric indicated that the Albanians had inhabited Dardania and Peonia before Slavs settled in these areas.

Autochthonous Albanian presence in Greece

filed under Albanians in Greece, Arvanites

Byzantinologue, A. A. Vasiliev would remark that in the first half of the fourteenth century, the Albanians for the first time began to play a considerable part in the history of the Balkan peninsula p. 613 At this time a strong movement of the Albanians toward the south began, at first into Thessaly, but extended later, in the second half of the fourteenth and in the fifteenth century, all over middle Greece, the Peloponnesus, and many islands of th Agean Sea. This powerful stream of Albanian colonization is felt even today. A German scholar in nineteenth century, Fallmerayer journied through Greece and found in Attica, Boeotia, and the major part of the Peloponnesus a very great number of Albanian settlers, who sometimes did not even understand Greek. If one calls this country a new Albania, wrote the same author, one gives it its real name. (pp. 613-615, History of the Byzantine Empire, 1964)

Click here to continue reading.Reviewed by Dr. Neritan Ceka, Professor of Archeology, Tirana University, Tirane, Albania (Translated from the Albanian Language by Arben Kallamata)

Anglo-Saxon scholarly studies have never shown any lack of interest in the ancient and large Illyrian populations although a complete and general work about them had never been published. That void is now filled in a very fundamental manner with the publication in 1992 of “The Illyrians” by John Wilkes, professor at University College of London. Prof. Wilkes, a well-known authority in this field especially because his previously published book “Dalmatia” (1969) – an important work on this Illyrian province of the Roman Era – has now been able to provide, combined with this latest book, the most complete synthesis of Illyrian culture and history available to date.

+ Continue reading

The book examines the origin of the Illyrians (The Search for Illyrians), their history in the framework of the Hellenic World (Greek Illyrians), their place and role in the Roman Empire, and, finally, the ethnic and cultural inheritance of the Illyrians during the Middle Ages to the present (Roman Illyrians). For the author, the first task was to establish the Illyrians as a large population that spread all over the Central and Western Balkans during ancient times. Prof. Wilkes criticizes, in a very objective way, existing theses that attempt to describe the Illyrians against the framework of contemporary political thought that either understates them through identification with an older concept of Illyrians as an undefined group of tribes, or by their ethnic and cultural unification over the entire period that they are mentioned in ancient times.

The diversity and unity of the Illyrian world is now explained in a more detailed manner by the author based on Illyria’s colorful and geographic identity in ancient times. It is this period, oriented towards a symetric division from the Danube, the Egean and the Adriatic Sea, that the author has been able to trace the different cultural groups that begin to take shape in an ethnogenetic process (beginning with the close of the Eneolitic period) to become quite distinct in almost twenty units during the Iron Age.

Based on the results of archeological research of what were identified as Illyrian regions over these last 100 years, a detailed study of the ancient onomasticis has been compiled by the author. His view, the distinction between a Venetian – not Illyrian – linguistic and cultural province as opposed to two large regions with Illyrian characteristics in the Central and Southwestern Balkans between Drava and the Adriatic Sea, is now presented. Within this work, the author also includes the largest part of Dardania in a discussion which is generally based on existing political biases.

The historical synthesis of the Illyrians is short and quite easy to comprehend. One can grasp the true meaning by comparing the historical geography of the Illyrian regions and tribes to the most significant events and characters. By their integration within this framework, the archeological data about Illyrian economies and the populated cities help define the historical and social basis in which the Illyrian state functioned previously, from the time of Bardylis to Gentius.

The section entitled Illyrians under Roman Rule , one of the most comrehensive parts of the book, focuses mainly on the northern parts of Illyria. Here, too, through archeological analytical studies, conclusions are highlighted thus making it possible to comprehend some of the most important aspects of the social and political organization in the north of Illyria during the pax-romana. Various aspects of Illyrian life are also revealed including dress, food, women, wine, and economic activities based on archeological documentation during the Roman Empire.

One of the most interesting chapters is how Illyria became integrated into the Roman Empire where its most significant result was the series of famous Roman Emperors who were of Illyrian origin such as Aurelianus, Diocletian, Constantine, and others.

The chapter “Medieval and Modern Illyrians” concludes with the historical destiny of the Illyrians where the author deals with the ethnic continuity of the Illyrians to the present day Albanians based mainly on the archeological findings of the Koman-Kruja cultural group.

It is only natural that such a broad overview of the Illyrians, which at times includes deep and competent analyses, is not always able to escape some shortcomings. In general, however, the weight of documentation derived from studies of the northern parts of Illyria (that are better known by the author) is more substantial although they have not always been the determining factors of Illyrian history and culture. As a consequence, a somewhat spontaneus explanation of historical events, influenced in part by an exaggeration of the role of Illyrian piracy, is more heavily stressed.

Also, Greek colonization is more closely examined through sites in the North than through the resistance and eventual integration processes of Dyrrhachium and Apolonia. In this vein even Gajtan, a prehistoric tribal center, is erroneously transplanted as representative of the settlements of the IV-III centuries (p.127), a period that was identified by civilian settlements such as Bylis, Dimalo, Lissus etc. to which the author accords a proper place in his book (pp.133-136). On the other hand, the association of Illyrian cities with the activities of Pyrrhus (V. Garasanin, Moenia, Aeacia, Starinar 17, 1966) is simply an exaggeration of an unproven concept. Similiarly, the invasion of Dyrrhachium by a Dardanian king called Monounios around 280 BC should be regarded as a factually unfounded hypothesis. It should suffice to mention certain other points where this rich material has eluded critical evaluation and absorption by the author. Despite these shortcomings, Prof. Wilkes’ book, enhanced and supported by many illustrations and a selective bibliography, has undisputable value as an important and fundamental history of the Illyrians.

Myth and reality about Kosovo

filed under Kosovo, Kosovo’s autochthonous population

Registration of land and population of Shkodra Sandjak in 1485 includes information on an area that extending between Tropoj, Junik and Gjakove, known as Altun-Alia. Areas to the north and south of this district were not included in the Shkodra Sandjak. This district included 53 villages with 926 households, 356 able-bodied men and 99 widow households. The register recorded the names of the heads of the families, the able-bodied and widows of each village that was responsible for dues.

In this essay I will focus on the main Serbian claim that Kosova was Serb and was populated by Serbs until the Albanians flooded in after 1690. This idea was put forth by a number of historians with J. Cvijic as their main representative. This myth took hold and inspired Serbian historians and politicians to this day. This is not the only anti-Albanian Serbian myth; on the same level is their claim that Kosovo was their cradle of nationhood, their claim of construction of churches (when in reality it was a takeover of existing churches) and their glorifying claim about the Battle of Kosovo (as if they were the only people that fought the Ottoman invasion), etc.

+ Continue reading

Unfortunately the Serbian and Greek mythical views dominated in the propaganda war for some time. This was due mainly to the inadequate Albanian effort to enlighten their history and also inadequate interest by foreign historians to challenge these claims. It was the Kosovar historians, M. Ternava, S. Gashi, I. Ajeti, R. Doci, L. Mulaku, R. Islami, and H. Islami who courageously challenged the Serbian view. Then followed the researcher S. Pulaha in Tirana, who researched Turkish archives for information about the ethnic status of the area at the time the Ottoman commenced. A summary of S. Pulaha’s findings follows: The registers of the census of the land and population of the Sandjaks in the 15th-16th centuries are important sources of information as to the population of the territories at the earliest stage of the Ottoman occupation, such as ethnic composition of the population, the degree of the implantation of timar system, as well as cultural effect the occupation was having on the people. On this occasion I will limit myself on the information these registers provide about the extension of the Albanian population in the territories of today’s Kosova/Kosovo.

Registration of land and population of Shkodra Sandjak in 1485 includes information on an area that extending between Tropoj, Junik and Gjakove, known as Altun-Alia. Areas to the north and south of this district were not included in the Shkodra Sandjak. This district included 53 villages with 926 households, 356 able-bodied men and 99 widow households. The register recorded the names of the heads of the families, the able-bodied and widows of each village that was responsible for dues. This period is reflective of the period of when Ottomans had just taken over the area and organized it administratively, and Islam had not as yet taken hold. Thus the names of the inhabitants reflect their religious affiliation prior to the conversion to Islam. The tendency being that the Catholics maintained their Albanians names while others had either Slavic names or a mix of Slavic-Albanian names.

Albanian researcher used this criteria in identifying the ethnicity of the inhabitats, and based on this, he stated the plain between Gjakova and Junik in the 15th century was without a slightest doubt a territory inhabited entirely by Albanians. He also adds that on the higher grounds, towards Tropoja, there were villages where the inhabitants exhibited Slavic names and Albanian names are not in preponderance. But at the same time, S. Pulaha observed, there were cases of Albanian families also used Slavic names. Here is how this phenomenon appears: Radosavi, son of Gjon; Vladi, son of Gjon; Bozhidari, son of Gjon; Gjorgj Mazaraku or Vulkashin Zhevali and Gjon, his son; Leka son of Mirosavi; Dejan, son of Gjon; Novak, son of Gjon; Ukca Stepani, son Leka Stepani and grandson of Stepan Leka; Milen son of Daba and his son, Lleshi the son of Milen; Gjon Bogoi and Ivan, his son; Lleshi son of Gjorgji, Tanushi son of Radsave; Bogdan, son of Novak, Dimitri, his brother, and Duka, his brother.

Pulaha indicates that there are many other such cases. There are also Albanian names with Slavonic adaptations, such as Lekac from Leka, Nikac from Nika, Dedac from Deda. More telling in this regard is information about the Vilayet of Kecova, located to the south of Altun-Alia which relates to the period of Bayazid the Second. The ottoman register divides Kercova into Albanian (arvnanvud) and Serb (serf) quarters. Pulaha indicates that the inhabitants of the Albanian section are indicated to bear not Albanian but Slavonic names. This would support the view that at this time Albanians also bore Slavic names, and it would be wrong, as some have done, to consider these inhabitants as being of Serb ethnicity.

S. Pulaha studied the 1582 (about a century later) Shkodra registers for the subject area and here is what he observed. The situation had not changed with villages that had indicated a predominance of Albanian names in 1485. In the villages of Shipcan, Gosturan, Cernomile, Stepaneselo, Trebnosh, where in 1485 Slavonic names predominated, in 1583, Albanian names predominate. In many other villages where Slavonic names were in use by the majority, such as Polja (Poliba), Shuma, Jasiq, Kovac (Kovacica), Goran, the number of inhabitants with Albanian names increased further. In some villages such as Sqavica, Rjenica, Miholan, Nebonani (Tebojani), Slavonic names continued to predominate in the 16th century as they did in 1485.

Pulaha indicates that a minority on inhabitants of areas analyzed above were exhibiting Islamic names in 1583. But the cities, on the other hand, had experienced a drastic increase in the population with Islamic names.

One of the most important elements of Balkan history has been the important role myths have played in history of some of the countries. It is a reality, the creation of Serbian and Greek (modern) ethnicities owe their creation to myths. These myths proved expedient during their national revival and afterwards, during which time they took precedence over national culture and state strategies. This is best exemplified by their anti-Albanian policies which were built on baseless myths. The intrusions into Albanian territories were given a totally different face and glorified. The autochthonous population did not fit at all in this scheme of things, of importance was only Serbian greatness in Kosovo and for the Greeks their idea of Greek Epirus.

As days of Ottoman Empire were coming to an end, the extremist elements devised plans to correct historic injustices that were bestowed on them and establish control over land they designated as belonging to them. Hence comes the myth that the Albanians had intruded to the land that belonged to them. To correct this historic injustice, extremist policies were devised against the majority autochthonous population of these territories. This population was subjected to a position of a people who had intruded on Serb and respectively Greek domains, and as such, even extermination policies would be acceptable. In this essay I will focus on the main Serbian claim that Kosova was Serb and was populated by Serbs until the Albanians flooded in after 1690. This idea was put forth by a number of historians with J. Cvijic as their main representative. This myth took hold and inspired Serbian historians and politicians to this day. This is not the only anti-Albanian Serbian myth; on the same level is their claim that Kosovo was their cradle of nationhood, their claim of construction of churches (when in reality it was a takeover of existing churches) and their glorifying claim about the Battle of Kosovo (as if they were the only people that fought the Ottoman invasion), etc.

Unfortunately the Serbian and Greek mythical views dominated in the propaganda war for some time. This was due mainly to the inadequate Albanian effort to enlighten their history and also inadequate interest by foreign historians to challenge these claims. It was the Kosovar historians, M. Ternava, S. Gashi, I. Ajeti, R. Doci, L. Mulaku, R. Islami, and H. Islami who courageously challenged the Serbian view. Then followed the researcher S. Pulaha in Tirana, who researched Turkish archives for information about the ethnic status of the area at the time the Ottoman commenced. A summary of S. Pulaha’s findings follows: The registers of the census of the land and population of the Sandjaks in the 15th-16th centuries are important sources of information as to the population of the territories at the earliest stage of the Ottoman occupation, such as ethnic composition of the population, the degree of the implantation of timar system, as well as cultural effect the occupation was having on the people. On this occasion I will limit myself on the information these registers provide about the extension of the Albanian population in the territories of today’s Kosova/Kosovo.

Registration of land and population of Shkodra Sandjak in 1485 includes information on an area that extending between Tropoj, Junik and Gjakove, known as Altun-Alia. Areas to the north and south of this district were not included in the Shkodra Sandjak. This district included 53 villages with 926 households, 356 able-bodied men and 99 widow households. The register recorded the names of the heads of the families, the able-bodied and widows of each village that was responsible for dues. This period is reflective of the period of when Ottomans had just taken over the area and organized it administratively, and Islam had not as yet taken hold. Thus the names of the inhabitants reflect their religious affiliation prior to the conversion to Islam. The tendency being that the Catholics maintained their Albanians names while others had either Slavic names or a mix of Slavic-Albanian names.

Albanian researcher used this criteria in identifying the ethnicity of the inhabitats, and based on this, he stated the plain between Gjakova and Junik in the 15th century was without a slightest doubt a territory inhabited entirely by Albanians. He also adds that on the higher grounds, towards Tropoja, there were villages where the inhabitants exhibited Slavic names and Albanian names are not in preponderance. But at the same time, S. Pulaha observed, there were cases of Albanian families also used Slavic names. Here is how this phenomenon appears: Radosavi, son of Gjon; Vladi, son of Gjon; Bozhidari, son of Gjon; Gjorgj Mazaraku or Vulkashin Zhevali and Gjon, his son; Leka son of Mirosavi; Dejan, son of Gjon; Novak, son of Gjon; Ukca Stepani, son Leka Stepani and grandson of Stepan Leka; Milen son of Daba and his son, Lleshi the son of Milen; Gjon Bogoi and Ivan, his son; Lleshi son of Gjorgji, Tanushi son of Radsave; Bogdan, son of Novak, Dimitri, his brother, and Duka, his brother.

Pulaha indicates that there are many other such cases. There are also Albanian names with Slavonic adaptations, such as Lekac from Leka, Nikac from Nika, Dedac from Deda. More telling in this regard is information about the Vilayet of Kecova, located to the south of Altun-Alia which relates to the period of Bayazid the Second. The ottoman register divides Kercova into Albanian (arvnanvud) and Serb (serf) quarters. Pulaha indicates that the inhabitants of the Albanian section are indicated to bear not Albanian but Slavonic names. This would support the view that at this time Albanians also bore Slavic names, and it would be wrong, as some have done, to consider these inhabitants as being of Serb ethnicity.

S. Pulaha studied the 1582 (about a century later) Shkodra registers for the subject area and here is what he observed. The situation had not changed with villages that had indicated a predominance of Albanian names in 1485. In the villages of Shipcan, Gosturan, Cernomile, Stepaneselo, Trebnosh, where in 1485 Slavonic names predominated, in 1583, Albanian names predominate. In many other villages where Slavonic names were in use by the majority, such as Polja (Poliba), Shuma, Jasiq, Kovac (Kovacica), Goran, the number of inhabitants with Albanian names increased further. In some villages such as Sqavica, Rjenica, Miholan, Nebonani (Tebojani), Slavonic names continued to predominate in the 16th century as they did in 1485. Pulaha indicates that a minority on inhabitants of areas analyzed above were exhibiting Islamic names in 1583. But the cities, on the other hand, had experienced a drastic increase in the population with Islamic names.

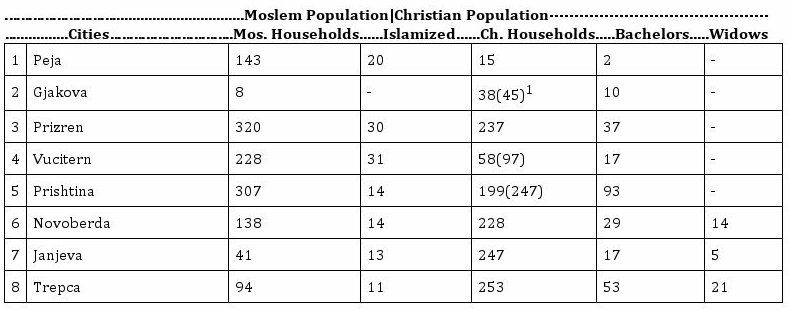

As we can see in Peja, Gjakova, Prizren, Vucitern, and Prishtina, the Moslem names of heads of families were in the majority (1006). By all indications this Muslim population consists of Albanian converts. That these converts were Albanian is seen by the retention of Albanian surnames by many. (See page 412) The Albanian ethnicity of this community is also ascertained by Papal envoys who visited these territories at the beginning of the 17th century. Pjeter Mazreku wrote (1623-1624) Prizren has 12,000 Turkish souls, nearly all of them Albanian; of this nationality only about 200 souls may be Catholic There are also about 600 Serbian souls. The archbishop of Tivari, Gjergj Bardhi, after a visit to the Dukagjini Plateau in 1638 said of this area, All these above mentioned places (in the Prizren-Gjakove stretch) are Albanian and speak the same language. Turkish geographer , Hadji Kalfa said that Prizren was inhabited entirely by Albanians. The renowned Turkish traveler, Evliyan Celebi, writing about Vucitern (16th Century) which he had visited, said that its inhabitants spoke Albanian, not Slavic, whereas the official language was Turkish.

Of the 547 Christian heads of family about 217 had Albanian or Albanian-Slav names and 330 heads of family had Slav Orthodox or Greek Byzantine religious sphere. By all indications, the former group was made up of individuals with Albanian ethnicity. At least part of the latter group must also be of Albanian ethnicity. The Serbian anthroponomy certainly was the effect of two hundred years of Serbian political and religious domination of Albanians. Under this reality, many Albanians adapted Serbian names, as they were to adapt Moslem names under Ottoman occupation. But the mass conversion to Islam would indicate that their ethnic dilution was not deep. As the Serbian control ended, Albanians renounced their Serbian names. The phenomenon of Albanians bearing Serbian names prior to the Ottoman occupation is attested by Mihail Lukarevic, a Dubrovnik merchant who had affiliations in Novoberda during the thirties of the 15th Century. His debtor’s books give a considerable number of people with Albanian names which point to the existence of an Albanian majority in this area. Along with people with purely Albanian names and surnames, there are also mixed Albanian-Slav names or Albanian names with characteristic Serbian suffixes.

In the cadastre books of 1455 in Vucitern and Prishtina areas following type names are found: Todor, son of Arbanas, Bogdan son of Todor; Radislav, son of Todor; Branislav, son of Arbanas (Kucica village); Bozhidar Balsha (Bresnica village); Radovan, son Gjon (Cikatovo village); Radislav, son of Gjon and Bogdan, his son (Sivojevo villages); Branko, son of Gjon and Radica, his brother; Gjoka, son of Miloslav (Gornja Trepz village), etc.

It is interesting to note that in the 1566-1574 register of Vucitern Sandjak, at location designated as Albanian quarters in Janjeva, nearly half of the inhabitants (84 heads of family and 8 bachelors) carried Slav Orthodox names. Thus, the section identifies as inhabited by Albanians, these inhabitants bore Slavic names or mixed Albanian-Slav names. This phenomenon is observed in many villages of Kosovo and as far north as Kurshumlia and Nish. The cadaster books indicate that not all Orthodox Christian inhabitants bore names from Slav Orthodox sphere. These names represented a heterogenous mixture of Albanian/Catholic names and names from Greek Byantine sphere, which are in wide use among the Albanians to this day. The Albanian character of this area is also attested by documents from the Command of the Austrian Army that entered Kosova in 1690 during the Austro-Turkish War. These documents point out that Prizren was considered capital of Albania. The Emperor Leopold I indicated that his armies were fighting in Albania (when they entered Kosova). The same documents indicate that the Austrian forces were met by 5000 Albanian insurgents in Prishtina and 6000 others in Prizren, thus basically confirming the preponderance of the Albanian population in this area.

It is clear that documents disprove the Serbian contention that Albanians had flooded into Kosovo after Serbian mass migration†northward in 1690. Above sources indicate that a century earlier, and most likely ever since the dawn of history, Kosova was inhabited by the same people,that is the Albanians. Any movement of population from Albanian mountains had to be minimal. In reality, based on these documents, Pulaha indicates, this was not even possible. It is indicated by the last census that between the end of the 15th century and the beginning of the 16th century, the population in the adjoining mountainous areas was very small (see pages 429-430).

***Source data and excerpts taken from Pulaha, S., Shqiptaret dhe Trojet e tyre, 1982, pp.334-452.

Contact Info

E-mail: gtcc.wb@gmail.com

Updates

Websites

Recent Bookmarks

Navigation